Employers at Walmart's Import Distribution Center in Elwood, IL

Employers at Walmart's Import Distribution Center in Elwood, IL

The nature of the employment relationship has shifted in a profound way. By some estimates one-third of US workers are no longer employed by their “real” boss. Instead, layers of subcontractors stand between workers and the firms that ultimately control the most important aspects of work life – scheduling, income, workplace safety, job security, freedom from discrimination and freedom of association. As David Weil, head of the US Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division shows in his recent work The Fissured Workplace, this shift has resulted in increased theft of wages, rising numbers of workplace accidents and widening income inequality.

This employment structure is increasingly becoming the norm in sectors from manufacturing to hospitality to food service. But nowhere is this shift more profound than in the warehouses that form the backbone of our nation’s vast retail distribution networks.

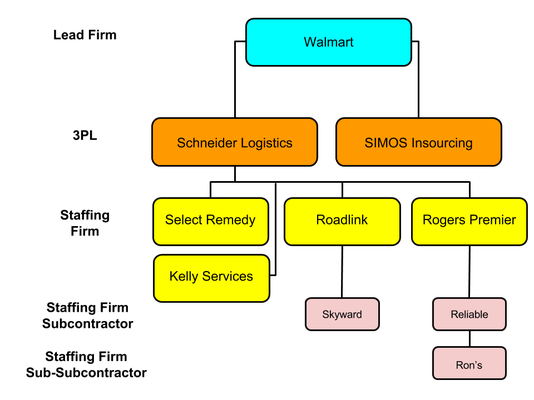

Although workers moving products for large retailers comprise the core of these firms’ downstream supply chains (Walmart, for example, is often termed by its investors not as a retailer but “a supply chain company that happens to have retail stores”) the workers in these facilities are often employed by a myriad of contractors and subcontractors, each competing to provide flexible labor at the cheapest cost. Most work either for third-party logistics firms (firms to which retailers and manufacturers outsource management of some or all of their supply chains) or temporary staffing firms.

Retailers award contracts on a regular basis to third-party logistics firms (3PLs) using an RFP process, typically awarding contracts to firms offering services at the lowest cost. These firms may in turn contract with one or more temporary staffing agencies to provide labor for particular job functions or areas of the facility. These agencies may themselves contract with other temporary staffing agencies or provide additional labor either on a short or long-term basis.

As a result, employees working in one warehouse as part of an integrated operation may work for one of several employers. For example, until recently workers at Walmart’s Import Distribution Center in Elwood, IL were split between ten different employers.

3PLs and staffing firms compete fiercely to acquire and retain contracts with retailers, leading to slimmer profit margins over time, and creating intense downward pressure on wages and working conditions.

This employment structure is increasingly becoming the norm in sectors from manufacturing to hospitality to food service. But nowhere is this shift more profound than in the warehouses that form the backbone of our nation’s vast retail distribution networks.

Although workers moving products for large retailers comprise the core of these firms’ downstream supply chains (Walmart, for example, is often termed by its investors not as a retailer but “a supply chain company that happens to have retail stores”) the workers in these facilities are often employed by a myriad of contractors and subcontractors, each competing to provide flexible labor at the cheapest cost. Most work either for third-party logistics firms (firms to which retailers and manufacturers outsource management of some or all of their supply chains) or temporary staffing firms.

Retailers award contracts on a regular basis to third-party logistics firms (3PLs) using an RFP process, typically awarding contracts to firms offering services at the lowest cost. These firms may in turn contract with one or more temporary staffing agencies to provide labor for particular job functions or areas of the facility. These agencies may themselves contract with other temporary staffing agencies or provide additional labor either on a short or long-term basis.

As a result, employees working in one warehouse as part of an integrated operation may work for one of several employers. For example, until recently workers at Walmart’s Import Distribution Center in Elwood, IL were split between ten different employers.

3PLs and staffing firms compete fiercely to acquire and retain contracts with retailers, leading to slimmer profit margins over time, and creating intense downward pressure on wages and working conditions.